Sweet Virginia: Why Data Center Developers Flock to Virginia

Intro:

Before data centers became the headline in tech real estate, Virginia quietly laid the groundwork: fast fiber-optic networks, competitive power pricing, and regulatory-friendly policy. These foundational advantages have made the state a magnet for data center developers. However, as other states rush to replicate the model, Virginia may be approaching a turning point.

The Virginia Advantage & Rising Demand

Virginia is home to more than 550 data centers (some estimates place it well above 600), with over 70 more in development. In particular, Northern Virginia’s “Data Center Alley,” which includes Loudoun, Fairfax, and Prince William counties, has become globally recognized for its density. Loudoun County alone contains nearly 300 data centers that draw more than 6 GW of power load.

Between July and December 2024, Dominion Energy’s contracted power commitments surged from ~21 GW to nearly 40 GW, an 88% jump in six months, signaling immense growth momentum. The state’s low power costs, favorable tax incentives (e.g. 6% sales/use tax exemptions on servers), and connectivity infrastructure (fiber/telecom backbone) have sustained its appeal.

However, this growth is bringing strains:

-

Rising residential electricity bills (Virginia’s rates increased ~47% from 2005 to present)

-

Grid reliability challenges (e.g., a 2024 disturbance where 60 data centers went offline during a storm)

-

Increasing local pushback and planning constraints: Fauquier County, Prince William, and Pittsylvania have all reviewed or denied rezoning or large data center projects amid community opposition.

-

Water usage stress: Data centers used ~2 billion gallons in Virginia in 2023, a 63% increase from 2019.

These dynamics suggest Virginia’s leadership may be facing recalibration as growth continues.

Before data centers were the hot topic everywhere, Virginia was already rolling out the red carpet, and it seemed that tech firms were constructing facilities as fast as humanly possible, drawn by the state’s robust fiber-optic network and low power prices. But while other states are racing to catch up, Virginia may be hitting the brakes. In today’s RBN blog, we’ll look at what makes Virginia so “sweet” for data center developers, their impact on the state, and efforts by some to slow progress.

This is our latest installment in a series examining the performance of some of the most popular states for data centers. As we discussed in God Blessed Texas, the Lone Star State, with more than 350 data centers, is one of the nation’s leaders, with only Virginia edging it out in both the number of data centers and associated power demand. Texas’ neighbor to the east, Louisiana, was initially slow in attracting developers, but now has two hyperscale projects being built. As we noted in Louisiana Saturday Night, state lawmakers changed laws to establish incentives for data centers and also used federal grant money to ramp up its fiber-optic network.

That brings us to Virginia, which is at the opposite end of the extreme from Louisiana. The state was the pioneer for data centers and has been home to them since the 1990s — long before most people even knew what a data center was. Dominion Energy, the state’s largest utility, reported in its February earnings call that its contracted data center capacity (i.e., future power commitments, not current load) in Virginia surged from about 21 gigawatts (GW) in July 2024 to nearly 40 GW by December 2024, reflecting an 88% increase over roughly six months. Dominion stated in February that its area within the PJM Interconnection market would experience a peak electricity load of 41.5 GW by 2034. (Dominion set a single-day peakload record of 24.6 GW in January.) To put that into perspective, the entire country of Italy consumed approximately 43 GW of power in 2023; the UK consumed around 34 GW in the same year.

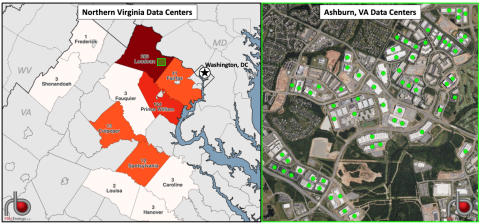

Virginia is home to more than 550 data centers (some estimates put the total well over 600), with at least 70 more in the planning stages. The northern part of the state (just to the west of Washington, DC) is a massive hub for data centers, especially Loudoun County (left side of Figure 1 below), which has nearly 300 data centers and accounts for more than 6 GW of power demand. The corridor — known as “Data Center Alley” — stretches across Loudoun, Fairfax, and Prince William counties and hosts the largest concentrations of data centers in the world. Loudoun County alone has more than 49 million square feet of data center space, with many sites clustered close together (green dots on right side of Figure 1) and many more under development. Loudoun County boasts that it has not had a single day without data center construction in more than 14 years.

Figure 1. Northern Virginia Data Centers. Sources: Google Maps, DataCenterMap.com

Note: Data centers are indicated by green dots on the right side of the map.

History of Data Center Growth

This brings us to the question of why Virginia began to attract data centers three decades ago, but the answer goes back even further. There’s a long history of technological innovation in Virginia that stretches back more than half a century. In the late 1960s, the Pentagon and the Arlington-based Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) launched ARPANET. It linked the Pentagon with major universities and showed, for the first time, that computers could communicate over long distances by breaking data into packets and routing them independently using hardware known as Interface Message Processors (IMP), which would send messages over long distances. Each computer connected to a local IMP, a type of early router. This planted the seeds for Northern Virginia’s future as a global hub for digital infrastructure. During the 1970s and 1980s, Virginia quietly built momentum. As ARPANET expanded, Virginia remained central to this network due to its ties to the Pentagon and defense contractors.

During that time, major defense contractors began to establish a presence in Northern Virginia, positioning themselves close to their government clients. Early investments were made in telecom switching, leased lines, and satellite operations. By the 1990s, momentum picked up quickly. Metropolitan Area Exchange East (MAE-EAST) was one of the first and largest internet exchange points in the country, and it put the Northern Virginia cities of Ashburn, Reston, and Vienna on the map. These sites enhanced network speed and connectivity, making the region more attractive to companies that required rapid and reliable data transfer.

Northern Virginia soon became the home base for early Internet leaders, including AOL, Yahoo, UUNET, WorldCom, and PSI Net. The dot-com bubble fueled expansion, and companies discovered they could build fiber-connected data centers in largely rural locations, where they faced fewer regulatory hurdles than in major cities. The area’s geography also helped, because it has a low risk of natural disasters, which is crucial for data centers handling critical operations. Following the dot-com bust in the late 1990s, the rise of cloud computing continued to drive momentum. Amazon Web Services, Digital Realty, and other hyperscalers arrived and began cementing the region’s dominance.

Another reason firms have flocked to Northern Virginia is that power has been comparatively cheaper there. In Loudoun County, the costs were once approximately 28% lower than the national average, although they are now about 14% higher, and rates are rising (more on this below). But the area’s advantages are solid. The Potomac River provides a reliable water supply for cooling systems, an essential need for data centers. Land has been affordable and available, and Virginia offers attractive tax incentives. The state’s sales and use-tax exemption saves operators around 6% on servers and other hardware. (For more on the factors influencing site selection, see Where You Lead I Will Follow.)

Data Center Challenges

While luring so many data centers has been pivotal to Virginia, it has come with a host of problems. Namely, the influx of data centers has contributed to higher electricity bills. From 2005 to 20, residential electricity prices in Virginia rose by approximately 47%, outpacing the national average increase of 39% during the same period. The state’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) projects that by 2040, data centers could raise the average household electricity bill by $14-$37/month, or $168-$444/year.

Most of Virginia’s electricity comes from natural gas, which fueled 55% of in-state generation in 2023, followed by nuclear at 32%, according to the Energy Information Administration (EIA). Virginia consumes more electricity than it produces, relying on imports from the regional grid to meet demand, according to the EIA. This heavy consumption places Virginia among the nation’s top 10 electricity consumers, despite its per-capita use being closer to the middle of the pack.

Dominion Energy has proposed rate hikes that will increase bills for households using 1,000 kilowatt-hours (kWh) per month from approximately $140 today to around $162 by 2027. These increases reflect higher fuel costs, rising demand, and investments to strengthen the grid, including support for the growth of data centers. The Virginia State Corporation Commission (SCC) began hearings on this proposal in September, with a decision expected by December. The proposed rate increase caused public outcry, and the Virginia Poverty Law Center urged the SCC to protect low-income households.

The buildup has also raised potential reliability issues. As we noted in Options Open, the region narrowly escaped an electricity crisis in July 2024 when 60 data centers using 1,500 MW of power suddenly dropped off the grid. A malfunction occurred during a thunderstorm, causing a transmission line to be locked out and resulting in rapid and significant voltage drops. These disturbances were brief but caused the data centers to get knocked off the grid. That triggered safety mechanisms designed to protect computer chips, but also caused a massive surge in excess electricity that could have led some systems to fail, prompting grid operators to take action to avoid widespread blackouts. The North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC), which focuses on grid reliability and security, expressed concern that similar issues could occur in the future.

Reining in Development

Because of these concerns, Virginia communities are taking matters into their own hands and asserting greater control over data center development. Earlier this year, in Fauquier County, the Planning Commission recommended denial of the proposed 800-MW Gigaland data center project. In August, the developers withdrew their application following massive community opposition and stated that they intend to submit a revised, scaled-down version of the project.

There are several additional examples. In August, a Virginia judge invalidated the rezoning approvals for the massive Prince William Digital Gateway, a project involving more than 35 data centers in Prince William County. In Pittsylvania County, the Board of Supervisors denied a rezoning request by Balico LLC, which proposed a 2,200-acre MegaCampus featuring 84 data centers and a 3,000-MW gas plant. In July, Tract, a Colorado-based developer, withdrew its rezoning application for a 744-acre, two-million-square-foot data center park in Chesterfield County after the Planning Commission unanimously recommended denial due to strong public opposition.

At the state level, lawmakers attempted to impose stricter regulations on data center siting and environmental assessments. However, Governor Glenn Youngkin vetoed key bills, including Senate Bill 1449 and House Bill 1601, which would have mandated more strict reviews. Despite these setbacks, counties are crafting their own legislation. In March, Loudoun County eliminated by-right development for data centers, requiring notable exception permits that require public hearings and board approvals. (By-right development allows construction that complies with established zoning and land-use regulations without discretionary approval from a local board or commission.) Similarly, Henrico County began requiring provisional-use permits for all new hyperscale data centers as of January.

Water usage remains a critical issue. Data centers in Virginia consumed nearly 2 billion gallons of water in 2023, a 63% increase from 2019, according to the “Data Centers in Virginia 2024 “ report by the Commonwealth of Virginia. Some facilities are adopting closed-loop cooling systems, which recycle water and can reduce freshwater use by up to 70% compared to traditional open-loop systems. (A number of the data centers we’ll discuss in our next blog in this series are planning closed-loop cooling systems.)

In the second part of this series, we’ll discuss the primary data centers currently planned in Virginia. While some areas of the state continue to welcome new development, it’s clear that some are ready to hide the welcome mat. Still, it’s clear tech firms are drawn to “Sweet Virginia.”

“Sweet Virginia” was written by Mick Jagger and Keith Richards and appears as the first song on side two of The Rolling Stones’ 10th studio album, the 1972 double album Exile on Main St. The country-flavored song is said to be influenced by country-rock figure Gram Parsons, who was present during most of the recording of Exile on Main St. It was recorded on The Rolling Stones Mobile Studio at Villa Nellcote in France, Olympic in London, and Sunset Sound in Hollywood. Personnel on the record were: Mick Jagger (lead vocals, harmonica), Keith Richards (acoustic guitar, backing vocals), Mick Taylor (lead acoustic guitar, mando-acoustic guitar, backing vocals), Bill Wyman (bass), Charlie Watts (drums), Ian Stewart (piano), and Bobby Keyes (tenor saxophone).

Exile On Main St. was recorded between 1969 and 1972 at The Rolling Stones Mobile Studio in Nellcote, France, Olympic in London, Stargroves in East Woodhay, UK, and Sunset Sound in Hollywood. Produced by Jimmy Miller, it was released in May 1972 and went to #1 on the Billboard 200 Albums chart. It has been certified Platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America. Two singles were released from the LP.

The Rolling Stones are an English rock band formed in London in 1962. The original group featured Mick Jagger on vocals, Brian Jones and Keith Richards on guitars, Bill Wyman on bass, and Charlie Watts on drums. Mick Taylor replaced Jones in 1969. Ron Wood replaced Taylor in 1976. Bill Wyman retired from the band in 1998, being replaced by touring bassist Darryl Jones. Charlie Watts died in 2021 and was replaced by touring drummer Steve Jordan. The Rolling Stones have released 31 studio albums, 39 live albums, 28 compilation albums, three EPs, and 122 singles. They have sold more than 250 million records worldwide. They have won five Grammy Awards, three MTV Video Music Awards, a World Music Award, and are members of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, the UK Music Hall of Fame, and have received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. They still record and tour. Their last release and tour, Hackney Diamonds, in 2024, was highly successful. Ron Wood has said the band is working on new tunes for their next release with producer Andrew Watt.

Unlock Strategic Insight in Hyper-Digital Infrastructure with Klean

Connectivity, Power, Scale — One Partner That Helps You Win in Data Infrastructure.

Virginia’s rise as a data center epicenter reflects deep infrastructure and policy advantage. At the same time, constraints are emerging. Klean Industries offers domain insight, site selection guidance, and cross-sector integration to help your digital infrastructure strategy stay ahead.

Klean’s Data / Infrastructure Advantage:

✅ Site Evaluation & Connectivity Strategy (fiber, latency, redundancy)

✅ Utility & Power Demand Forecasting & Modeling

✅ Regulatory & Incentive Strategy Navigation

✅ Risk & Reliability Assessment (grid, water, permits)

✅ Advisory Support from Location Strategy through Execution

With Klean’s deep systems perspective across energy, infrastructure, and circular economy, your infrastructure and data projects will be resilient — not reactive.

Ready to explore data center strategy in Virginia (or beyond)?

You can return to the main Market News page, or press the Back button on your browser.